Anna Atkins: Innovative Victorian Scientist & Cyanotype Artist

Happy Birthday Anna Atkins! Today, March 16th, 2021, is Anna Atkins’ 222nd birthday!

If she were alive today, Anna Atkins would likely call herself a scientist--a botanist to be exact. When she died in 1871 at the age of 72, she had gained a good deal of respect in the scientific community. Yet most modern historians recognize her as the first female photographic artist. So how did a botanist become a photographic artist? It all revolves around one woman’s ingenuity, her passion for plants, and an early photographic process called the cyanotype.

Anna Atkins (1799-1871)

“A.A.” (Anna Atkins or Anonymous Artist?)

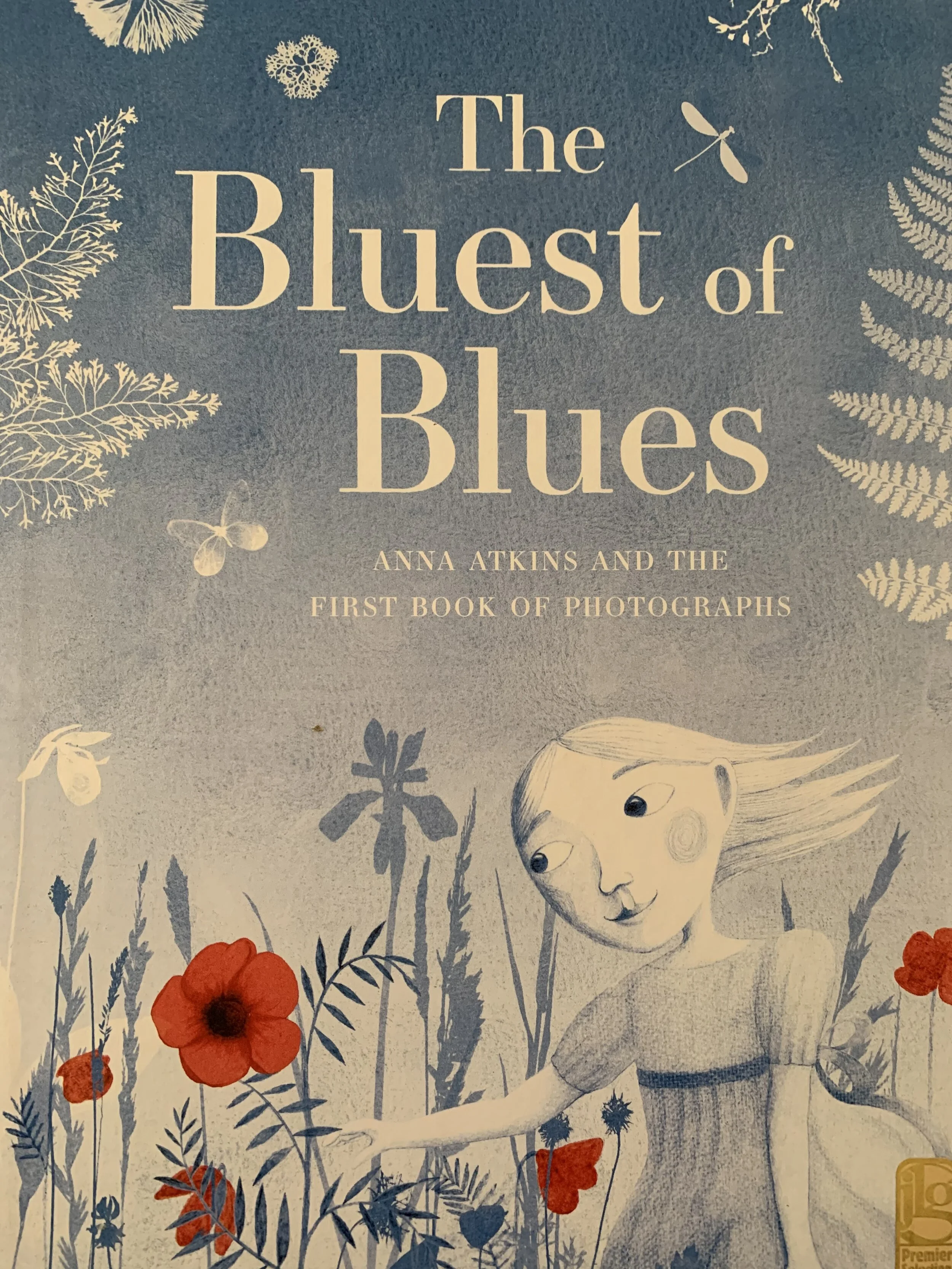

Information about Anna Atkins’s life can be hard to find. And what does remain was essentially ‘lost’ until fairly recently, due to a case of mistaken identity. It seems that many historians had assumed the “A.A.” that Atkins used to sign her work stood for “Anonymous Artist”. However, a careful study by historian Larry Schaaf in the 1970s, finally revealed the truth. Since then, Atkins has gained a good deal of respect and admiration. Although information about Atkins is still spotty, I did find one fantastic source in an exceptionally beautiful children’s book called Bluest of Blues: Anna Atkins and the First Book of Photographs, by Fiona Robinson.

Bluest of Blues

Bluest is primarily historical fiction, of course, but Robinson has taken all those threadbare historical bits and woven a rich and dreamy tale--which is probably not too far off from the truth. The story opens with a young Anna and her father exploring an English meadow ‘thick with butterflies and bees’. Anna’s arms are full of wildflowers and her father carries a bug jar and field guide. The story highlights the special bond that Anna had with her father, John George Children, her primary caregiver. Anna’s mother had died shortly after she was born, so Anna’s father (who had also lost his mother at an early age) lovingly raised her and cultivated in her a deep love of science.

George Children was himself a scientist, a chemist and mineralogist. He was a member of the Royal Society of London, an esteemed scientific community, and was also head of zoology at the British Museum. He taught Anna all about the scientific method of classification and encouraged her skills in scientific illustration. Anna’s father would remain a source of inspiration and admiration throughout her life. After he died, she wrote his biography and he described him as having an “earnest warmth of heart which neither the winter of adversity nor of age could ever chill.”

A Passion for Plants

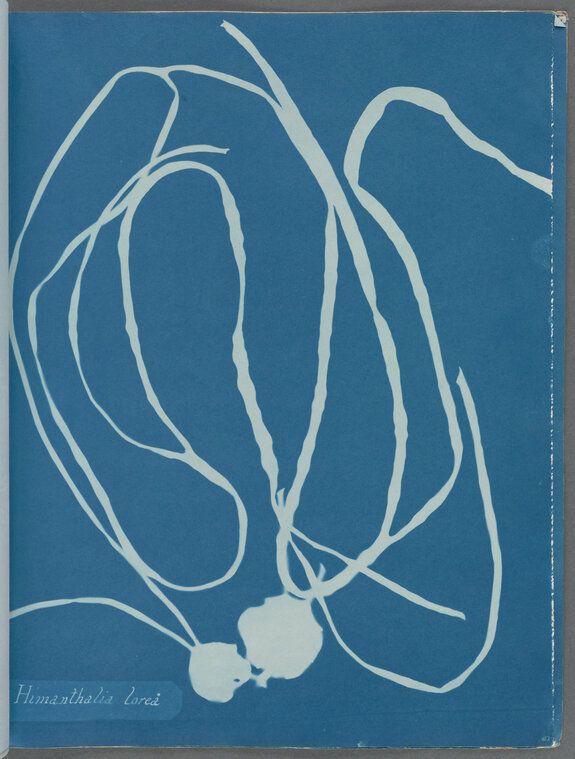

By the time she was in her 20s, Anna was an illustrator and botanist. Because she was so passionate about plants, she set about creating an extensive herbarium. Her prized seaweed collection alone contained some 1500 specimens. As a dedicated scientist, she knew the collection had important instructional value as a scientific tool and she longed to publish it. Nevertheless, she knew the task of illustrating such a volume, even with her skill as an illustrator, was both time and cost prohibitive. Enter Sir John Herschel--inventor, astronomer and, neighbor!

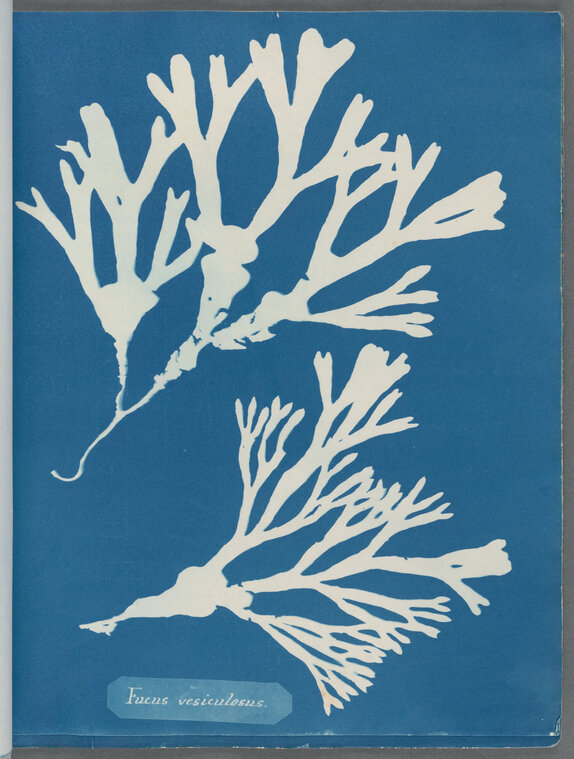

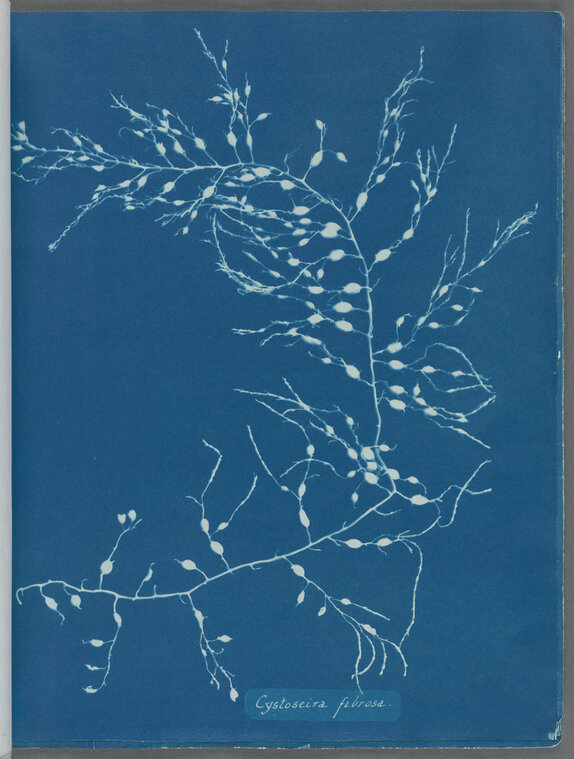

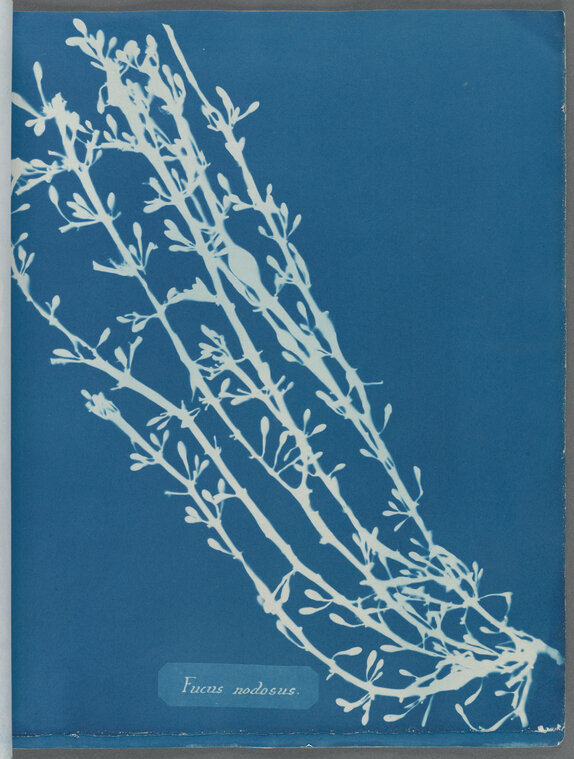

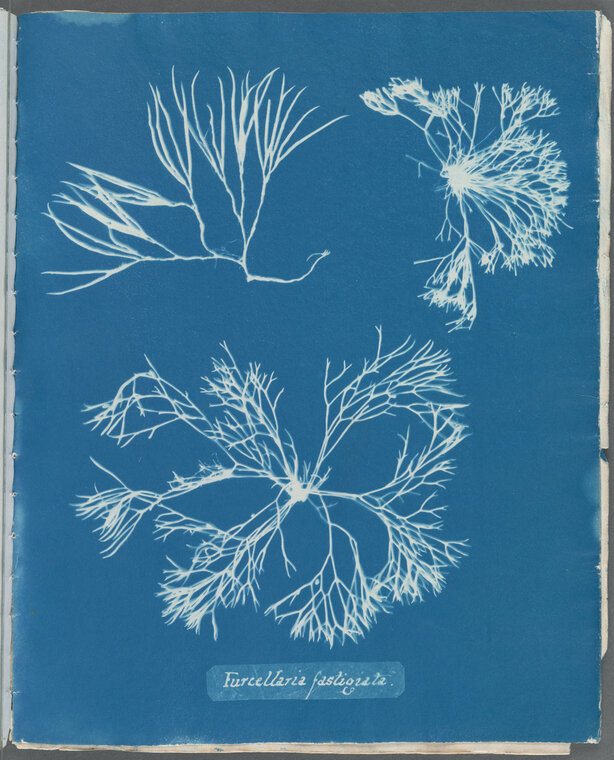

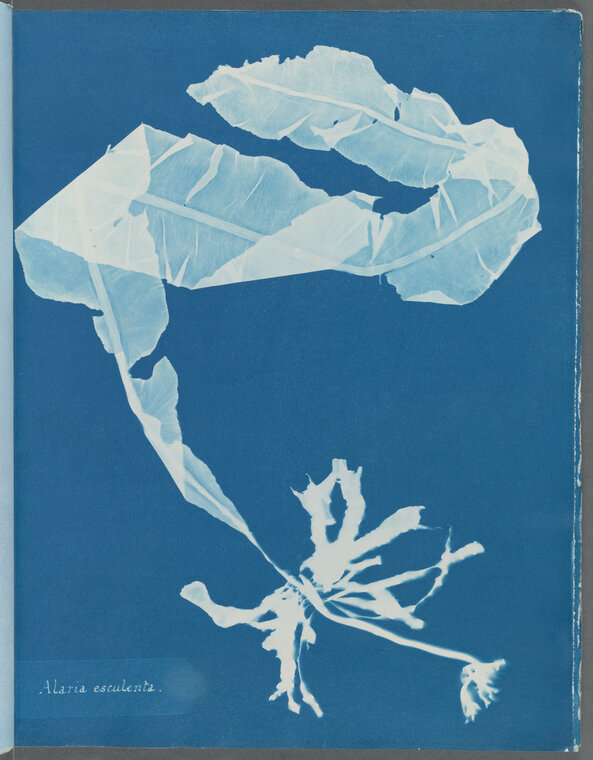

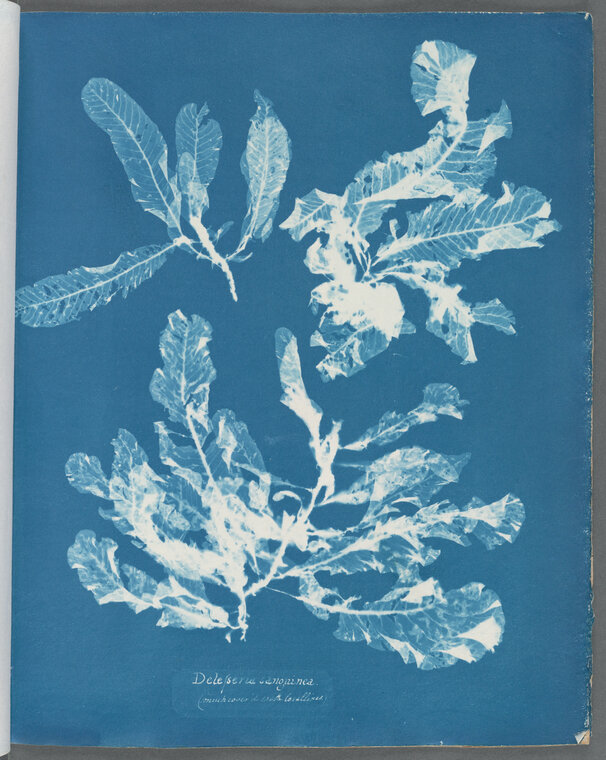

Herschel was interested in experimenting with light sensitive chemicals to develop a method for copying his astronomy notes. And since necessity is often the mother of invention, he ultimately discovered the cyanotype, or blueprint process. The cyanotype process uses light sensitive chemicals to capture the silhouette of an object on paper (learn more about the process here).

As their neighbor and fellow scientist, Herschel was close to Anna and her father and introduced Atkins to the process. It didn’t take long for Anna to realize the potential of the process and she soon realized that she had stumbled upon the perfect way to document and publish her beloved seaweed collection.

She wrote, “the difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects so minute as many of the algae and confervae has induced me to avail myself to John Herschel’s beautiful process of cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves…”

The First Book of Photographs

So she soon set about the painstaking process of making a 3 volume book set. In 1843, Atkins’ diligence finally paid off and she produced her first book called, British Algae, which she dedicated to her beloved father. The book holds the distinction of being the first ever book of photographs.

Attkins went on to make copies of her three volume set for friends and dignitaries, including one for her dear friend and mentor, Sir John Herschel. The work involved in creating each set is staggering. Keep in mind that each photograph in the book was handmade, making each a unique original. Each book in the set contains about 400 cyanotypes, which amounts to a total of some 1200 per set. Incredible. No one knows exactly how many sets she made in total, but 17 volumes remain to this day.

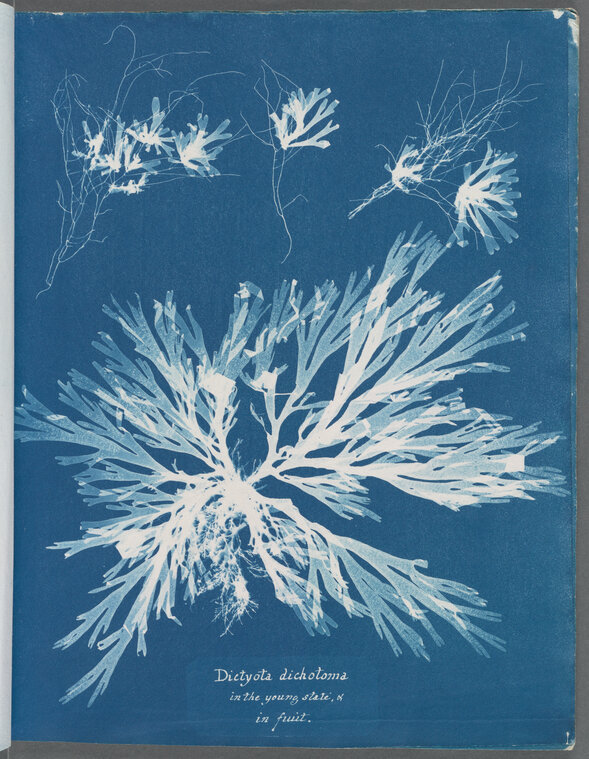

Atkins went on to create other photographic books later in life. With the help of her dear friend Ann Dixon, she produced, Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853) & Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns (1854). She also wrote three books of fiction.

First Female Photographer?

So was Anna Atkins the first female photographer? Many scholars credit Constance Fox Talbot, wife of James Talbot with the title of first female photographer. But we will never know for sure, because photographs from that time period lacked a fixative so any images captured eventually faded away. It’s safe to say, however, that Anna Atkins was definitely among the first women known to experiment with photography. As it turns out George Children was friendly with James Talbot, who invented the photographic process in 1841, and Anna’s father gave her a camera that very same year. So we know she was experimenting with photography even before she began working with cyanotypes.

Without a doubt though, Atkins certainly deserves the title “first female photographic artist”. While it is clear that she worked as a dedicated scientist, and that her aim in publishing was to create a scientific tool, we certainly see hints of Anna as artist in her first book. Take look at the title and you will see that she artistically created the letters out of seaweed! Her later work with Ann Dixon takes a decided shift towards the artistic. Her work at that time reveals many playful, layered compositions of lace and feathers and ferns and poppies.

I hope you have enjoyed learning about Anna Atkins. Her story is an important one—not only for her contribution, but also for the sheer will and determination it took to actually make a contribution at a time when women’s work was largely unappreciated and ignored. So Happy Birthday Anna Atkins! We are so glad your story has endured and your legacy continues!

Resources

If you are interested in learning how to make a cyanotype yourself, check out my tutorial here. It’s fun to do and if you like plants, I think you will enjoy both the process and the results. I’m sure Anna would be pleased to know that her influence still has reach some 200 years later.

See more of Anna Atkins’ work at the NY Public Library’s digital collection.

You can find a copy of Fiona Robinson’s Bluest of Blues at your favorite bookstore. It would make a beautiful addition to any child’s library and the sweet little tutorial in the back of the book is perfect for encouraging future botanists to connect to nature in a new and enchanting way.